"Unsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial Imagination," an Interview with Dr. Taylor Eggan

May 06, 2022

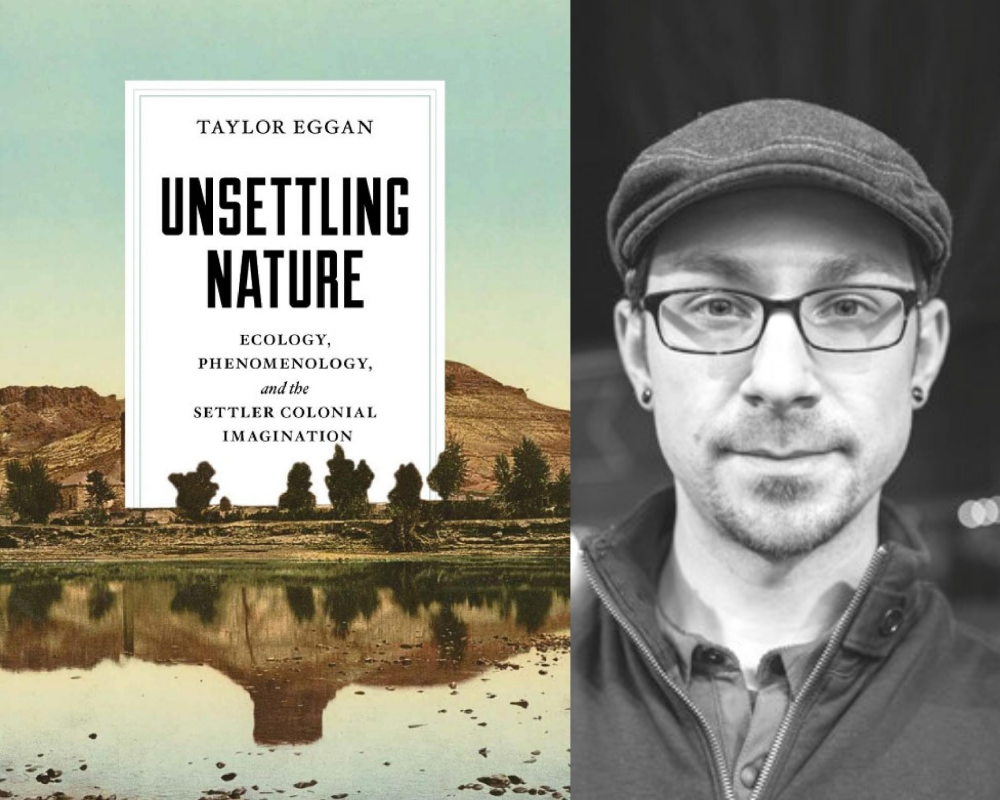

This week, we sat down with Assistant Professor in PNCA at Willamette's Hallie Ford School of Graduate Studies, Dr. Taylor Eggan, to discuss his latest publication, "Unsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial Imagination" (UVA Press, 2021).

An exhilarating deep dive into Eggan's ideas about nature, identity, home, and belonging that are interwoven in the book, this conversation also clarifies some of Unsettling Nature's strongest arguments, namely that some of "our most beloved and comforting ideas about home have a dark side." I hope you enjoy Eggan's insights as much as I did.

To read more about the book or purchase it for yourself, follow this link to UVA Press. And without further ado . . .

Can you start by saying a bit about the book and what it’s up to?

On the most general level, Unsettling Nature concerns a series of interlinked issues related to concepts of nature, home, being, and belonging. In the book I engage closely with philosophy, literature, and history in order to tell the complex story of how these concepts get tangled up with one another in problematic and destructive ways, particularly when uncritically deployed in settler colonial contexts. As a part of this story, I address questions related to (1) how we perceive nature, (2) how we link our perceptions of nature to an affective experience of home, and (3) how the resulting concept of home enables us to make certain imaginative claims about belonging in or to a particular place.

The “we” I’ve referenced just now deserves some comment. I write as a white male settler of Anglo-Norwegian descent, who has lived his whole life in a yet-to-be-decolonized settler colony. Therefore, this “we” refers most directly to those who, like me, continue to benefit most from the genocidal settler colonial project that Europeans initiated in the sixteenth century and have presided over into the present moment. But the “we” I’m using here will also apply, in varying degrees, to any settler touched by the logics of settler colonialism—which is to say, any and all of “us” who occupy Indigenous lands and who enjoy the literal and figurative fruits of that occupation. Settlers come from all sorts of backgrounds, and each will have their own unique configuration of privilege and relationship to the white hetero-patriarchal norm. But settlers “we” remain.

One thing that links many (though not all!) of “us” settlers together is our collective attachment to the places we call home. This attachment is a key difficulty that gets in the way of our ability to imagine what decolonization might look like. Understandably so. It’s all too easy for many settlers to see decolonization as synonymous with our own displacement. And not just a metaphorical displacement from whatever sense of power we believe ourselves to possess, but something even more harrowing—the actual, literal displacement from our homes. Furthermore, I hasten to add that home is an unusually flexible concept that applies as much to our physical houses as to the particular landscapes, cities, regions, nations, states, and countries we inhabit. Because of this flexibility, the settler fear of displacement from the home must also be understood as an anxiety about losing a whole series of nested, place-based identities.

At the core of this settler anxiety there lies, I think, a question about the legitimacy of “our” belonging. This isn’t a question we tend to pose consciously. Instead, many of us develop various strategies to repress our anxieties about belonging. We may deny culpability for the actions of our ancestors. We may cite the apparent inefficacy of political action to renounce present responsibility. We may even call attention to the ways our sexual orientation, gender expression, ethnic origin, or experience of racial marginalization distance us from the center of power and privilege. In every case—and yes, I myself have personally felt tempted by each—we seek to diminish our complicity.

There are many strategies we might use to repress our settler anxiety. But the strategy my book takes up centers on perceptual and imaginative processes by which settlers transform space into “our own particular beloved place”—a phrase I borrow from Terence Ranger, the great historian of British colonial Rhodesia. By retraining our senses to align with our desire for a space of comfort and belonging, we make ourselves at home.

Would you mind saying a bit about how nature fits into all of this? The book’s title clearly indicates that ecology is a major preoccupation, so how does nature relate to the concept of home and settler colonial strategies of repression?

In my research, I was struck again and again by a certain uncritical appeal that I felt was silently undergirding a lot of environmental thinking. Motivated by a mix of modern alienation and desire for radical revitalization, this appeal established a fundamental link between the concepts of nature and home. To paraphrase: nature is understood as a sort of primordial dwelling place that humanity has long ago left behind and to which we must somehow return. And, by first restoring ourselves to this primordial dwelling, we humans may yet find a way to save the planet from the convulsing crises that we have ourselves created due to our alienation from the natural world. Or so the basic logic goes.

The area of environmental thinking where I found this logic most predominant was an influential field known as “eco-phenomenology.” As that name indicates, eco-phenomenology is a strain of environmental philosophy that is deeply influenced by the great twentieth-century tradition of phenomenology, which includes many notable figures such as Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Emmanuel Levinas, among others.

Now, some casual readers may find that word rather esoteric, just as some academics might consider the term old fashioned. But in truth, eco-phenomenology has made its way into a lot of popular environmental thinking and nature writing, particularly through the work of David Abram, whose books The Spell of the Sensuous (1996) and Becoming Animal (2010) have both found impassioned readerships. And though not many academics would use “eco-phenomenology” as a frame anymore, there is much evidence to indicate the deep influence this field continues to have on the strands of environmental philosophy that dub themselves “eco-hermeneutics” and “eco-deconstruction.”

But my point isn’t really to defend the relevance of the term “eco-phenomenology.” Instead, my purpose is twofold. First, to identify the central position that field has given to the concept of home. And second, to confront the field’s tendency—sometimes explicit, more often implicit—to predicate saving the planet on a prior and more radical “homecoming” to our primordial dwelling on the Earth. Saving the planet by returning to the primordial dwelling: this is what I refer to as the ecological homecoming narrative.

Without getting too much further into the weeds here, I’ll just finish by saying that one of the book’s central aims is to unravel the complex knot that entangles this ecological homecoming narrative with the kinds of settler homemaking strategies I mentioned earlier. I would say that the bulk of of Unsettling Nature is attempting to get at the historical and even metaphysical nuances that link the idea of coming home to nature with the settler desire to repress anxieties about belonging.

What critical conversations do you hope this book will start? What do you hope changes in your readers, as they read your book?

I really like the way you’ve phrased this question—it’s less aggressive than, say, What intervention do you want to make with this book? And though I think I wrote the book with a focus on making certain critical interventions, your question helps me see that at its deepest heart the work does seek opening more than closure. Let me see if I can orient my answer toward what the book opens up.

Broadly, I want this book to open a conversation about how our philosophical ideas and ideals so often get tangled up with the politics that invisibly make those idea(l)s possible. In my case, I’m talking about how some of our most beloved and comforting ideas about home have a dark side.

Now, the critique I’m after isn’t exactly new. Many others have written about, say, the Nazi ideal of the homeland, or Heimat, which was all about an essentialist notion of Aryan descent. Only those of pure German blood were worthy enough to inhabit pure German soil.

But I’m trying to make a broader argument than this. The Nazi example locates the problem of homeland thinking in an exemplary instance of white supremacy. And because, looking back, we tend to focus on the Nazis’ extermination of those with the wrong blood, we tend to forget the blood’s supposedly essential link to soil. It’s precisely this link that I’m interested in. But as my research proceeded, the decolonial theorists I was reading reframed how I understood this example. These theorists increasingly convinced me that the Nazi ideology was just one manifestation of a deeper “coloniality” that had a much greater historical and geographical reach—originating as it did with the Spanish voyages to the New World in the sixteenth century, and metastasizing over the centuries to shape our global modernity.

Now, that’s a huge idea, and one worked out in much greater detail by a range of decolonial thinkers I cite in the book. In drawing on this work, my somewhat humbler aim is to show how the fantasy of nature as primordial dwelling proved integral to the kinds of settler homemaking projects that continue to shape life in my two major areas of study: the U.S. Southwest, and southern Africa.

In the U.S. context, for instance, it’s well documented that Manifest Destiny was legitimized by the astonishing beauty of the land’s natural resources. This is the basic story of how the U.S. National Park system got built. European settlers arriving at what we now call Yosemite (or Yellowstone, or Zion) could be said to have “come home” to an earthly paradise that had been lost but which they, good and deserving Christians, must reclaim from the savage Natives. With that in mind, I hope my book will also contribute to a discussion of what I might call the “affective inheritance” of settler colonialism. In this regard I hope that readers—and particularly settler readers—will begin to think more critically about what’s involved in the big feelings they likely experience when passing through the Great American Landscape.

Unsettling Nature ends with a meditation on how settlers can develop a “decolonial sensorium” that is more acutely attuned to one’s own settler identity—a position that remains unmarked and unremarked by most settlers. How can we feel more like the settlers we are, then act in the world in ways responsive to and responsible for that feeling? More generally, how can we speculate beyond the limits of our current experience in ways that don’t simply expand our own personal worldview, but that actively make room for the various othernesses that always interpenetrate our world, whether we recognize it or not?

These questions provide the book’s final opening for the readers, who I hope will feel empowered by the invitation to enter.

What aspect of this text are you most proud of? Have you watched yourself grow as a writer/researcher, throughout the process of publishing it?

I think I’m most proud simply of having found the fortitude to stick with the many years of research, writing, and rewriting that go into a book like this. I can’t overstate how challenging (practically, existentially) such a commitment can be in the face of modern life’s many instabilities.

I’m glad that you ask about growth as a writer/researcher, because I think prolonged projects like this both necessitate and force growth. This book began as a Ph.D. dissertation, then underwent a somewhat radical change as I reimagined it for publication as a monograph. I surprised myself in being as flexible and eager as I was to transform much of my earlier thinking. Yet I also found that so much of the magic of sustained projects like this comes from precisely

Tell me the love story between you and academia. What pushed you to decide to train as a professor and scholar? What’s kept you around?

“Love” might be too strong a word for how I feel about academia, haha! That said, I really do love working closely with students who are pursuing their own research. There’s a vitality to those exchanges that naturally arises from the experience of thinking your way into the unknown, together.

Aside from that, I think what’s kept me engaged has been my growing sense that scholarly writing is, in fact, a profoundly creative practice. A lot of folks tend to dismiss scholarly writing as removed from the world, entrenched in jargon, and endlessly (even pointlessly) engaged in critique. But if you look at a lot of what’s being published today with university presses, I think there’s a great deal of creative ferment and boundary pushing. No longer is scholarly writing so tightly bound to narrow institutional horizons. I’ve found in my own practice that scholarly research and writing entail various forms of creativity at every level, and I take greater heart in the work the more I lean into the possibilities of experimentation.

Who are you reading right now?

I’m a pretty omnivorous reader, and I usually have a little too much on my plate. Just now I’m about halfway through a very slow, canto-a-day reading of Dante’s Divine Comedy. I’m also making my way through Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s wonderful Prix Goncourt–winning novel from last year, La plus secrète mémoire des hommes (“The most secret memory of men”).

In the past couple years I’ve been teaching myself Norwegian, which is my family’s heritage language. To accompany that study, I’ve been reading a lot of Norwegian writing—mostly in English, but also consulting the originals when I can get my hands on them. I dubbed this past winter my “Winter of Ibsen,” and though we’re in spring now, I’m still working my way through all his major plays, as well as an excellent biography by Ivo de Figueiredo. More contemporary writers I’ve read lately include Hanne Ørstavik, Dag Solstad, Gunnhild Øyehaug, and my personal favorite, Tarjei Vesaas. Right now, I’m reading the gosh-wow-good third volume in Jon Fosse’s Septology, recently out in Damion Searls’s translation from Transit Books.

That’s some of what I’m pursuing in my “personal” reading practice. My current “professional” reading has me immersed in Paul Celan’s poetry, Craig Dworkin’s work on experimental poetics, and Min Hyoung Song’s innovative new book on climate change-centered reading practices.

Do you have any upcoming projects?

I’m currently preparing a chapter on the Ethiopian American writer Dinaw Mengestu for the forthcoming Routledge Handbook of the New African Diasporic Literature, edited by Lokangaka Losambe and Tanure Ojaide.

I’m also in the midst of two new book projects. One is somewhat unrelated to this material, and perhaps at too early a stage to talk about publicly. But the other is a sequel of sorts to Unsettling Nature, and which embarks on a series of methodologically idiosyncratic forays into what I’m calling “speculative perception.” My working definition of speculative perception is still pretty broad. For me, the central emphasis is on metacognitive practices that are experimental and curiosity-driven, and which seek to fold critical reflection into our perceptual and affective experiences of the world at large.

About the Book

The German poet and mystic Novalis once identified philosophy as a form of homesickness. More than two centuries later, as modernity’s displacements continue to intensify, we feel Novalis’s homesickness more than ever. Yet nowhere has a longing for home flourished more than in contemporary environmental thinking, and particularly in eco-phenomenology. If only we can reestablish our sense of material enmeshment in nature, so the logic goes, we might reverse the degradation we humans have wrought—and in saving the earth we can once again dwell in the nearness of our own being.

Unsettling Nature opens with a meditation on the trouble with such ecological homecoming narratives, which bear a close resemblance to narratives of settler colonial homemaking. Taylor Eggan demonstrates that the Heideggerian strain of eco-phenomenology—along with its well-trod categories of home, dwelling, and world—produces uncanny effects in settler colonial contexts. He reads instances of nature’s defamiliarization not merely as psychological phenomena but also as symptoms of the repressed consciousness of coloniality. The book at once critiques Heidegger’s phenomenology and brings it forward through chapters on Willa Cather, D. H. Lawrence, Olive Schreiner, Doris Lessing, and J. M. Coetzee. Suggesting that alienation may in fact be "natural" to the human condition and hence something worth embracing instead of repressing, Unsettling Nature concludes with a speculative proposal to transform eco-phenomenology into "exo-phenomenology"—an experiential mode that engages deeply with the alterity of others and with the self as its own Other.

About the Author

Taylor Eggan teaches in the Hallie Ford School of Graduate Studies at PNCA. He is a literature scholar whose work engages broadly with postcolonial literature and theory, environmental philosophy, phenomenology, translation studies, and the history of the novel. He is also a movement-based artist who seeks to bring somatic awareness to intellectual pursuit.